In the ever-evolving landscapes of web3 and Internet of Things (IoT), a revolutionary concept has emerged, challenging the traditional paradigms of connectivity and paving the way for a decentralised future. Enter DePIN, or Decentralised Physical Infrastructure Network, an innovative framework that stands at the intersection of decentralised technologies and the Internet of Things.

In this article, we will delve into the distinctive value proposition offered by “DePINs” in contrast to existing solutions. Additionally, we will explore some key challenges that projects may face as well as the key elements that we are looking out for projects building in this vertical.

Understanding DePINs: Origins and Market Potential

Messari coined the term DePIN, short for Decentralised Physical Infrastructure Network, in late 2022. This term accurately describes web3 protocols that bring together and provide services or resources from a decentralised network of physical machines, incentivised via a token model.

To understand the significance of DePIN, it is essential to dive into the origins and evolution of the IoT itself. The inception of the IoT dates back as early as the 1980s. The foundational concept revolved around integrating computing capabilities into ordinary objects, enabling them to communicate with each other. As the internet grew rapidly from the early 2000s, the surge in connected devices prompted a demand for standardisation. Led by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the Internet Protocol (IP) became the framework for data transmission across networks. Newer iterations of IP are continuously developed over time, and the latest IPv6 pushes the boundaries of the current infrastructure by being able to support the ever evolving demands of the internet.

The rapid expansion of the internet has brought forth various challenges — such as security and privacy issues emerging as some of the key concerns. The interconnected nature of devices poses a significant risk whereby one vulnerable device can potentially compromise the entire network. Data breaches are one of the most common instances of IoT vulnerability, which has experienced a significant uptick from the mid 2010s onwards in the US. This has provided compelling reasons for the exploration of decentralised alternatives to protect the dynamic and evolving IoT landscape.

While the IoT space advanced, the pursuit for enhanced efficiency persists. This drive gave rise to Helium — a decentralised wireless network designed to improve connectivity and equitable user participation. In an oligopolistic domain, the emergence of decentralised alternatives presents a valuable opportunity for both users and potential founders. This sparks healthy competition and the possibility of better products. The IoT market is growing fast, expected to double in revenue within five years, potentially exceeding $2 billion by 2028. Thus, these decentralised alternatives, or what we know as “DePINs” certainly have incredible potential to grow over the next few years.

Navigating the DePIN Spectrum: From Physical Machines to Digital Resources in Web3 Evolution

In the dynamic landscape of DePINs, the definition spans a broad spectrum. Blockchains themselves could be considered in line with the DePIN concept. Operating through miners or validators within a decentralised network, they ultimately provide the crucial resource known as “Consensus.” The notion of DePIN might have been present since the beginning of decentralised networks with Bitcoin’s theorisation, gaining official recognition only recently.

To offer clarity, mapping DePINs across a spectrum becomes essential. This spectrum spans from decentralised networks of physical machines, highlighting hardware specificity and software agnosticism, to decentralised networks of digital resources, emphasising software specificity and hardware agnosticism.

Many of these decentralised resource networks trace back to a Web2 counterpart, as they aim to resolve existing issues more efficiently. However, some were created to fulfil on-chain specific needs. Such solutions were either not possible or not needed in the web2 world. For example, Oracles like Chainlink are product offerings unique to Web3. They enable smart contracts to execute based on data from the real world, by using a decentralised network of independent oracle node operators to retain the trustlessness of the system.

The debate arises on whether solutions like Chainlink can be considered DePINs. This hinges on one’s interpretation of the physicality of nodes/service providers in the network, often run on independent machines. However, the more crucial consideration is the value these decentralised networks bring over their centralised counterparts. By focusing on the strengths of decentralisation, the hope is to guide Web3’s evolution into creating real substantial value for the masses.

Value Proposition of DePINs in general

Now that we have covered the What, it’s time to explore the Why. There are 3 main stakeholders in every DePIN protocol which will highlight the value propositions:

- Demand Side Users (Consumers of the Resource)

- Supply Side Users (Providers of the Resource)

- Protocols themselves (Team and Investors)

Taking into account all stakeholders involved, the decentralisation effect can brings forth three distinctive value propositions of DePINs:

1. Economic Efficiency from Underutilised Resources

The primary and most crucial benefit of DePINs lies in the economic advantages they offer, benefiting all stakeholders involved. The significant economic efficiency derived from decentralisation comes from the ability to harness globally idle resources that would otherwise go to waste.

In the case of decentralised computing — idle servers, GPUs, CPUs (supply side) around the globe now have an avenue to monetise their assets as they depreciate or become obsolete over time. At the same time, DePIN protocols (middleman) can curate these computing resources globally at a lower cost of integration and operation, and offer these aggregated resources to users who need them (demand side) at a lower price. This also means that fungible resources like computing power and bandwidth can be more uniformly available across the globe, not only because of lower costs but also because of the removal of the need to set up infrastructure everywhere.

The market size of global cloud computing stands at 633 billion (USD), with an anticipated compound annual growth rate of 16% projected from 2023 to 2032. Companies are spending hundreds of thousands to millions just on cloud computing needs depending on the use case, which can be drastically reduced via distributed computing.

For example, Akash is a decentralised network of cloud service providers that can aggregate and provide this required cloud computing power to developers at a lower cost. Through decentralisation, this service can be efficiently curated and offered at around an 80% discount compared to traditional centralised players like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure.

Another potential source of economic efficiency is the ability to identify performance differences across nodes for different use cases. Certain nodes may specialise in producing/procuring certain resources and the DePIN protocol can intelligently allocate work to match each node’s strength. This efficiency is analogous to the economic efficiency brought about by trade globalisation, whereby each country naturally specialises in producing a set of resources, then trades with one another for resources they do not specialise in, creating an overall more efficient global economy. This once again lowers costs for the protocol and demand side users, as well as allows supply side users to focus on providing what their asset does best instead of trying to optimise for everything.

2. Lowering Barriers for Stakeholders & Geographic Entry

DePINs revolutionise market entry dynamics by significantly reducing barriers for both resource providers and new projects, fostering a more inclusive and dynamic ecosystem.

Ease of Resource and Service Entry

DePINs simplify the process for resource and service providers to join, eliminating unnecessary hurdles and welcoming those meeting the DePIN criteria. This streamlined approach has proven effective, drawing in diverse contributors and strengthening the DePIN network. Storj’s success, boasting a more substantial provider base than Filecoin, exemplifies the positive impact of this accessible entry process.

Adaptable Growth Across Regions with Localised Solutions

DePINs can effectively scale across diverse jurisdictions simultaneously. By utilizing incentives, DePINs can grow their network easily, bypassing the traditional expansion process of a centralized entity. Additionally, DePINs can leverage their decentralized structure to offer tailored resource solutions in various geographic and demographic communities. This flexibility ensures that resources are universally accessible and highly relevant to specific local market needs.

Hybrid Scaling with Centralised Provisioning

DePINs can employ a flexible scaling approach, incorporating both decentralised and centralised resource provisioning. For instance, Storj optimizes scalability by centralising access and database management through Storj’s controlled satellites. This strategic hybrid model enables individual operators to secure the network with minimal infrastructure, resulting in a higher onboarding success rate, as evident in Storj’s substantial provider base (~514k) compared to Filecoin (~3.8k).

In essence, by lowering barriers and embracing a hybrid approach to scaling, DePINs foster a more inclusive, globally responsive, and dynamically adaptive ecosystem for resource providers and project developers alike.

3. Governance and Security

The decentralised networks also allow for implementing better governance systems. Users who are invested in DePIN protocols on both the supply and demand side can have their voices heard via voting on and opening governance proposals. This allows decisions to be made in the best interests of all stakeholders and facilitate proposals that are synergistic for stakeholders. In contrast, centralised systems make decisions driven solely by investors, who are more focused on their personal financial returns.

Trustlessness, security, and liveness of resource provision are inherent in DePINs. They come without incurring the high costs associated with security and high-quality infrastructure that is required in a centralised system. A DePIN network can maintain service provision even if some nodes are down. In contrast, centralized service providers face single points of failure, which can lead to significant disruptions if there’s a breakdown or compromise in their systems. In 2022, various cloud service outages occurred, such as Google Cloud’s increased latency in January and Slack’s three-hour outage in February. Centralised providers, like AWS, faced a two-hour outage in July 2023 due to a power outage. While uncommon, the likelihood of the majority of nodes in a DePIN network going down or being compromised independently is much lower, providing a better liveness and security guarantees.

However, ensuring these benefits truly provide value to stakeholders necessitates proper measures. There are also some factors and obstacles that DePINs may face that should be considered when building a DePIN, which are also what DWF Ventures looks for in a DePIN protocol.

Potential Hurdles and Factors to Consider for Success

While DePINs do have the potential to bring about immense value to both demand and supply side users on the resources we have today, there are several factors that we look for that make up a successful DePIN project.

Some key factors to consider:

- Scaling Performance Capabilities to Match Centralised Players

- Ease of Onboarding and Adoption

- Alignment of Tokenomics and Incentives

1. Scaling Performance Capabilities to Match Centralised Players

With the economic benefits addressed, DePINs also have to ensure competitiveness in terms of performance as compared to centralised players. The performance of a DePIN protocol is what drives demand side adoption, which in turn can encourage supply side adoption. There are three main ways performance of a DePIN protocol can be managed:

- Hardware and Software Specifications

- Addressable Demand

- Location Sensitivity and Density

Hardware and Software Specifications

Hardware and Software specifications pertain to the requirements that supply side participants need to meet in order to provide resources or services at a satisfactory quality. DePINs can require specialised devices/programmes to ensure consistency in quality of service, or allow for compatibility with more commonly owned devices like mobile phones or laptops. Requiring a specialised device/program improves reliability and uptime for end users, but would act as an additional barrier to entry for service providers. In most cases, performance is prioritised, as any barriers to entry are usually worth the cost or effort for service providers if demand for the service is strong as a result.

Projects could also opt to become the exclusive distributor of their specialised device/program or collaborate with third parties to outsource production/development. Outsourcing could foster competition, potentially resulting in enhanced capabilities and lower costs for providers. However, there are risks of quality issues if production becomes too fragmented across different providers, or potential supply shortages if providers are not able to meet the project’s requirements.

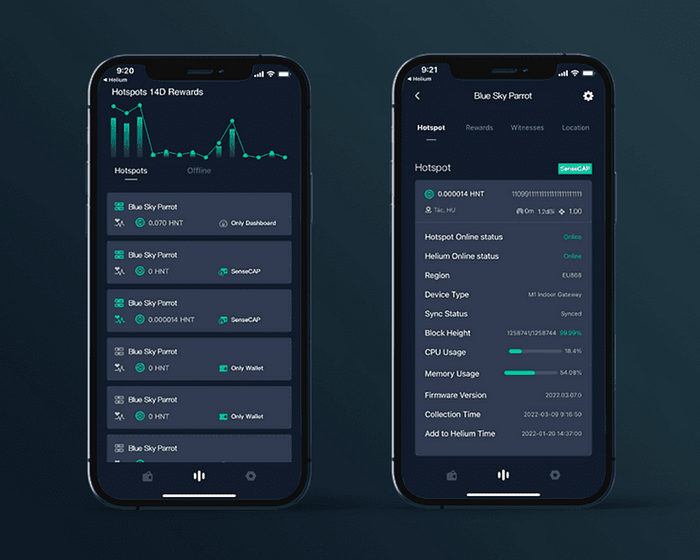

For example, Helium started out with creating their own hotspots back in 2019 but only managed to onboard around 15k hotspots by the end of 2021. A proposal passed in early 2021 allowed for third party manufacturers to come onboard as long as they meet the requirements, which likely contributed to the exponential growth in hotspots from early 2021 to 2022. Helium now has over 28 manufacturers onboard, which helps in decentralisation and offers users a wider range of options as well. One of the cheaper hotspots can be obtained from Sensecap at just ~$130, significantly cheaper than the original Helium hotspot which costs around ~$495.

Addressable Demand

One aspect that many DePINs lack compared to their centralised counterparts is the full suite of features that these more established players offer. Centralised Cloud Service providers like AWS provide their users with a large ecosystem of tools for deploying their application and developing their product, whereas many DePINs today are more focused on a single service, like computing power or data storage. This shows the amount of potential for the DePINs space to grow to match the range of capabilities of centralised solutions.

OORT is taking a step in that direction, providing both decentralised compute and storage facilities by building a network of service providers for different use cases vertically and horizontally. OORT does this by having 3 tiers of service providers:

- Archive Nodes: Data Storage nodes from Filecoin, Storj, Crust, and Arweave.

- Edge Nodes: Network of OORT issued devices with home PC capabilities for decentralised computing.

- Super Nodes: Public and private cloud service providers like Tencent Cloud, Alicloud, Seagate, etc. for higher end compute and storage requirements.

This means that OORT can offer a full suite of cloud computing services while retaining the benefits of decentralisation, as any need for intense or simple compute and big or light data storage can be fulfilled by one or more of the 3 tiers of service providers.

Location Sensitivity and Density

For some projects, achieving a sufficient level of user density within a specific geographic area is crucial to ensure the effectiveness and practicality of the service they offer. This is similar to what co-location is in traditional technology. It is particularly significant for services that rely heavily on location-based data and interactions, such as mapping services or ride-hailing platforms.

For mapping services like Hivemapper, having a high concentration of users in a particular region is essential for the platform to provide accurate and up-to-date information which would impact utilisation of the product. For example, most of Hivemapper’s coverage is currently centred around the US and a few European countries. With coverage being fragmented in areas like East Asia, Hivemapper created bounties as part of the targeted mapping initiatives in MIP-2. Additional rewards were reserved for allocation on areas listed in the proposal to encourage building fuller coverage for those areas. This is key in allowing Hivemapper to even be comparable with centralised alternatives.

Similarly for ride-hailing services, having a sufficient number of both drivers and riders in a specific area is crucial for ensuring an optimal experience for both. A higher density of drivers means shorter waiting times for riders and more ride options for them to choose from. An example of this is Drife, which has focused its efforts on onboarding drivers to the platform in Bengaluru and has onboarded over 10000 drivers to date. This ensures that riders achieve a better user experience such that there will be recurring demand for rides to match the supply of drivers. Thus, achieving sufficient density in a certain geographical area is critical for increasing the performance of the service.

2. Ease of Onboarding and Adoption

The initial phase of a provider’s engagement with the network is the onboarding process. While hardware specifications play a role, the steps following the acquisition of the necessary hardware are important as well. Once the setup is completed, providers must monitor the hardware to ensure that the necessary conditions for earning rewards are met. Projects that require passive or active management from providers will impact the number of providers incentivised to join.

For example, setting up Helium hotspots is relatively straightforward for most users. For providers utilising Sensecap, an intuitive process involving turning on the device and configuring bluetooth is sufficient to start earning rewards. Although there is a one-time set up fee of $15, it abstracts away the complexities of interacting with the blockchain, making it more appealing to a wider range of potential providers. Providers using the app can easily monitor the status of their hotspots in one interface, ensuring that they remain operational will allow them to earn rewards passively.

In contrast, projects like Spexigon would require users to take on an active role in the project to earn rewards. After acquiring the specified drone (DJI Mini 2 which costs around ~$339), users have to personally fly and capture imagery from their location while ensuring that they are compliant with local regulations. Furthermore, since Spexigon is focused on capturing imagery across different geographical areas, a user’s earning potential may be limited by their surrounding environment. Thus, the number of users that can be onboarded to Spexigon are limited by a multitude of factors — from onboarding, regulations to the need for active utilisation of the drone to earn rewards.

In general, an easily navigable and swift onboarding procedure will allow the project to reach a broader audience. Nonetheless, this is contingent on the project’s specific requirements and priorities. This factor would be more important for services that benefit from a higher quantity of providers such as Helium, over the curation of high quality providers.

3. Alignment of Tokenomics and Incentives

The last important factor that DePIN protocols should plan out carefully is the utility and value flow enabled by token mechanics. A great product needs an equally good token model to ensure all stakeholders are incentivised in a way, which allows the token to properly reflect the value of the project.

To begin we can look to Chainlink for a tried and tested token utility model to determine a base token framework for DePINs. In the case of Chainlink’s token utility model, the stakeholders are similar to any decentralised resource network:

- Demand Side Users (Spender of Tokens)

- Supply Side Users (Receiver and Staker of Tokens)

- Team and Investors (Token Holders)

Demand side users pay LINK token for Oracle services, while supply side users get LINK token in exchange for their service. This creates demand for tokens in a way that is directly related to demand for the offering.

Supply side users are also required to stake tokens as collateral to guarantee service quality, or face slashing penalties. This encourages higher quality service and creates demand for tokens that is directly related to the aggregated quality of service by all service providers, which itself is dependent on demand for the offering — higher demand encourages higher quality service from more service providers.

Finally, token demand benefits token price, which is what token holders are looking for. This creates more demand for the token from investors in the secondary market.

From this we can see that demand side users will care least about the token price, while the team and investors care the most. Supply side users are in the middle, given that they also have certain exposure to token prices via their staked tokens. Regardless, this framework creates a scenario where all the stakeholders play a role in supporting token price.

Token emissions also have to be planned out. In most cases, token emissions exist as part of early incentive campaigns to attract users. With the 3 stakeholders in mind, it would make sense to spread token incentives across the 3 stakeholders based on how difficult the project thinks it is to attract those users to the network. Of course, with token emissions comes inflation, so projects also have to think of how to manage token emissions and burns. Projects also have to be careful not to rely too heavily on token emissions to incentivise demand side users, as these users should be first and foremost attracted by a superior product offering, which is where the ball starts rolling. Generally, token incentives should focus more on attracting supply side users to fulfil the demand for a superior offering.

Some DePINs also allow demand side users to make payment in other ways. This will not affect token demand as long as payments received are used to buy tokens to pay supply side users. Effectively, this simply gives demand side users the flexibility to choose their payment channel.

For the protocol itself, revenue can come from taking a share of the payments from demand side to supply side users, or charging membership or licensing fees to demand side and supply side users respectively. These revenue streams can be used to cover operating costs, and any excess can be used to further increase token demand via revenue share or buyback and burn mechanisms. Projects can also require token holders to stake tokens or provide liquidity to benefit from revenue share to stabilise token prices or boost liquidity.

Shaping the Next Era of DePINs: What we are looking out for

At DWF Ventures, we believe that the success of a DePIN project lies in the incorporation of specific elements. These elements include tailored hardware specifications that align with the project’s resource demands. Additionally, a robust incentivization model, coupled with well-structured tokenomics, is crucial for sustaining the project’s ecosystem. Prioritising the creation of an optimised user experience for both supply and demand-side participants is important as well. This ensures that the project is able to attract and retain users, ultimately contributing to the project’s overall success and longevity. These combined factors lay the foundation for a successful and sustainable DePIN initiative.

Currently, we see that existing DePIN projects mostly have the first three elements well-established, as most are predominantly geared towards incentivising supply side users. Understandably, as supply side users are pivotal for the initial network expansion. However, it is still important to dedicate substantial resources into developing a good product that genuinely garners demand — not just simply being a decentralised alternative for an existing service.

Nonetheless, the entire DePIN ecosystem is still relatively nascent. Despite having projects that have been established for years, we anticipate that there will be more innovation and potentially the rise of a game-changing protocol in this vertical.

For projects actively building in this space with products that can meaningfully impact the market, feel free to reach out to DWF Ventures. Interested parties can pitch their project on our website at https://www.dwf-labs.com/ventures.